|

the

earth-mother's

|

|

IRISH

PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE

ending Prehistory. .

|

|

Stone forts or cashels (Irish caiséal from Latin castellum) are the most impressive surviving monuments of the Iron-age, now Celtic-speaking, inhabitants of Ireland. The introduction of iron weapons and the structural changes of society evidently led to a great increase in cattle-raising, hence cattle-raiding and warfare - for cattle were the real unit and source of wealth. Even today it is cattle that the Irish love, not the land they overgraze. Gradually, people would have had less time, inclination and opportunity to erect even simple stone kists - because they were building fortified, kraal-like farmsteads and refuges which, in rocky, treeless areas, or when built by the powerful, were of stone. Because very few tall, fair-haired Celts actually made it to Ireland in fact rather than in myth (e.g. Fíonn Mac Cúmhaill and his flaxen-haired Fíanna), Ireland is much less 'Celtic' than, say, France or Germany (since the Celts and the Teutons are hardly distinguishable). Nevertheless, Celtic culture made a huge impact upon the island, not least in language - which was imported rather as English was later imported, over time - and in structures made of stone which still survive. The most characteristic of these are the cashels and stone forts. Grianán of Ailech, county Donegal Many cashels, however, are not easily defensible: often one side of them is extremely vulnerable. But they very frequently afford fine views. This suggests that they were built more for status than for defence, and possibly they acted as observation-posts - rather like today's fashion for cargo-cult bungalows with a view onto the road and with a prestige hand-built dry-stone wall fronting it. Their dating is difficult, but most of those that survive were built well after the first century BC. Many were built or kept in service right into the mediæval period - the period when the Anglo-Normans and the English continued the traditional method of rule in Ireland: a few immigrants speaking a new language and with new customs, who lorded it over the ethnically-mesolithic population (stocky, swarthy, brown-eyed, brachycephalic) as had the Neolithic farmers. Stone forts in general assume various forms, the simplest being the Promontory-forts which are stone walls across the necks of coastal promontories on which other defences and buildings might be constructed in wood and/or stone. Inland promontory-forts cut off mountain-spurs in a similar fashion. Dunbeg promontory-fort, county Kerry More sophisticated ones do not actually cut off a promontory but occupy a cliff-top higher than the surrounding ground, as at Dún Aonghasa on the Aran Islands. This fort has a chevaux-de-frise of thousands of stone obstacles as a further protection against attack Dún Aonghasa, Inishmore, county Galway - with surrounding chevaux-de-frise Like the cashels proper, promontory-forts could they be very large and complex structures covering up to a hectare or more, but, unlike many cashels, definitely occupy defensible positions. Of the cashels (more or less circular stone-walled forts) the largest concentration is in the Burren of county Clare, and in the maritime counties from Cork clockwise to Antrim. Many have wall-chambers, stone staircases and terraces, as well as remains of round huts. Most of these were, unfortunately, over-restored by fanciful engineers towards the end of the nineteenth century, and should be admired with a little scepticism. Dún Conor, Inishmaan, county Galway A few vitrified forts - well-known in Scotland - have recently been identified in the North of the island. These had a timber framework, which, when set alight, produced such an intense heat that the stones started to melt into a kind of glass. This may have been done deliberately, to solidify the rampart.

Aerial view of the Burren limestone plateau with a typical stone fort.

Doon Fort, county Donegal Such artificial islands - known as Crannógs (from crann = tree, timber, wood) - occur in their thousands all over Ireland, but rarely bore anything so massive as a cashel. They are now mostly covered with trees.

A typical tree-covered crannóg in Lough

Ramor, county Cavan,

Mostly they were built with brushwood and branches weighted with stones, and defensible corrals were constructed so that cattle could be driven over and protected during unsettled (that is to say most) times right up to the late mediæval period. They are not large and would have been refuges for just one extended family and its cattle. A fisherman (in the foreground) at Lough-na-Cranagh

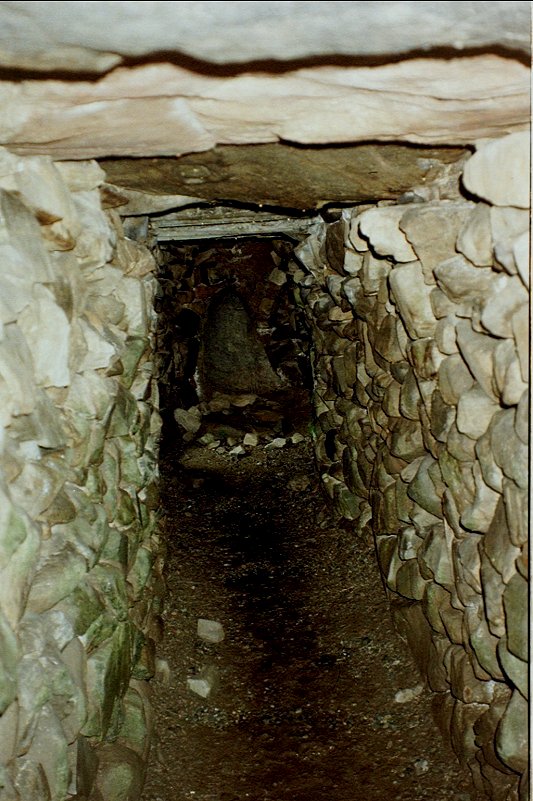

on top of Fair Head, Associated with stone forts, but also occurring in huge numbers all over the maritime counties, are Souterrains or underground passages which served as places of safe storage of foodstuffs and valuables, of refuge, and secret means of entering and leaving defended places, particularly during the period of Viking/Norse raids in the ninth and tenth centuries - though some were built (and destroyed) as late as the thirteenth century. In the 5th century AD Ireland had undergone a radical change which transformed the nature of the Irish settlement and made a lasting impact on the natural environment. Pollen records testify to a huge upsurge in grasses and weeds associated with pasture and arable farming - indicating a revolution in the landscape which involved the clearing of forests - a process which continued to its bleak and treeless climax right up to the 19th century. This was also the time when Christianity gradually seeped into the island, and closer contact with the ex-Roman world to the East was established. Irish agriculture "improved" and thus population increased with the increased food production. This increase in population lead to the construction of literally tens of thousands of fortified farmsteads known as 'ringforts' or (from the Irish) raths which provided some security from marauding neighbours and raiders from farther afield. Towards the end of the first millennium the fortified farmsteads started to become obsolete, possibly because ring-fort defences were useless against marauding Vikings, who had moved warfare onto a different plane, and who were keen not just on sacking the rich monasteries of the East and Centre, but on establishing settlements along the coast. As the ringforts vanished, the souterrains appeared and proliferated: a desperate innovation in defensive architecture. They can be simple passages, sometimes roofed with suitable and convenient standing-stones or ogam-stones, or they can be complex labyrinths with defensible 'creeps' or stile-like obstacles. Thousands must have been mere underground tunnels. Several souterrains were dug into the passage-tomb at Knowth, and one can still be seen at Dowth, county Meath.

Exposed souterrain revealing roof-lintels. A souterrain partly-roofed with ogam stones (removed

ones erected on either side)

The passage of a souterrain at Drumena, county Down.

The entrance to a souterrain at Ballybarrack,

just outside Dundalk, county Louth,

A part of the souterrain complex at Ballybarrack

during excavation

Another detail of the Ballybarrack complex showing

a defensive trap The most common of all ancient constructions in Ireland are the farmhouses, known as raths, always circular and with banks which once supported palisades. There are at least 10,000 of them, all over the country. Some contain souterrains or remains of stone structures. They are not listed in this field-guide, but below is a photograph of a fine example on the Dingle Peninsula, with a by-road skirting it, and remains of a structure inside.

Doonclaur, county Kerry. |

Click on the thumbnails for high-resolution pictures.