IRISH

CROSS-PILLARS

and cross-slabs

part one

text and photographs by

Anthony Weir .

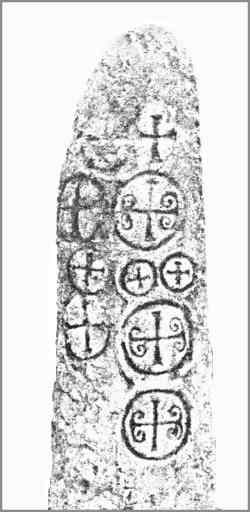

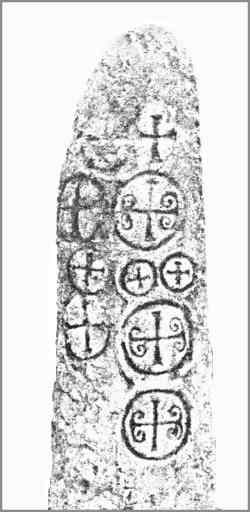

Kilnasaggart, county Armagh: detail of Christianised

pillar-stone

(south side)

For a full view in colour

of the inscription on the north side, click on the image above.

Just as Ogam

inscriptions were added to already-standing stones of considerable

antiquity, so, with the remarkably peaceful Christian penetration

of Ireland, menhirs and sacred boulders attracted Christian appropriation.

Dunfeeny, county Mayo

Although

the largely-legendary St Patrick is credited with overturning

'idols' all over the island, in the unique and traditional

Christian manner, it may have been just as satisfying in the 6th

century - and much more permanent - to Christianise a 'pagan'

stone as to destroy it. As late as the 19th century 'pagan'

stones removed by priests had a propensity for returning to the

spot.

Lankill, county Mayo

Some of

the Christianisations had a distinctly prehistoric look, suggesting

that the Irish church (which was nothing like the modern Catholic

church, but much more like the Coptic and Syrian churches) was

rather more receptive and assimilative than others in Europe.

Cross-pillar inside the entrance

to a stone-fortified farmstead,

Knockdrum, county Cork. This type of cross is called a cross-pattée.

By and

large, the inhabitants of Ireland welcomed this tolerant form

of Christianity, with its fantastic redemption, as a relief from

the dark rites and realistic fatalism of Celtic religion.

Kilvickadownig, county Kerry:

a design on a boulder

which incorporates an A for Alpha (the foot of the cross-pattée)

and an Omega (W ) forming a curclicued

nimbus around it.

Celts

had holy stones and holy wells and worshipped trees, streams,

groves, glades and genii loci. Irish Christianity seemed

to be able to accommodate all these except the trees - and it

was with the proliferation of wealthy monasteries from the eighth

century onward (and the Norse attack that they attracted) that

the first serious deforestation since Neolithic times occurred.

Ireland, like Scotland, was largely covered with deciduous and

holly-tree forest.

It is now the most-deforested country in Europe.

Kildreelig or Killerelig,

county Kerry

Irish Christianity was essentially monastic and almost federal,

whereas Catholicism is episcopal, hierarchical and totalitarian:

"E pluribus unum"! The Irish church had no Rome-appointed

head until St Malachy of Armagh went to Rome in the 12th century

and had himself appointed Archbishop.

While

large monasteries were established on the fat cattle-lands of

the East of Ireland

Sun-dial, Bangor  county Down

county Down

and around

the central Bog of Allen which covered a great deal of the interior,

little monasteries were established in remote places, often called

Diseart or Dysart, after the Latin Deserta.

Monks modelled themselves on the early Desert Fathers, amongst

whom the first monks of all, St Paul the Hermit and St Anthony

- and successors such as St

Onuphrios - were models for those few who went off

to solitary spots, often on islands or islets, and subsisted on

seabirds, sea scurvy-grass and shellfish while praising the glory

of God as presented to them by wild and spectacular Nature.

A monastic settlement, containing clochans

or stone huts,

and resembling a promontory fort, on an island off the North shore

of the Dingle Peninsula.

Below: a typical clochan, which would have housed

one or a few monks..

All over the island, monks found, carved and erected cross-pillars

for themselves.

click

to  enlarge

enlarge

Pillar and Tomb-shrine with armhole for

touching the bones of St Buonia,

Killabuonia, county Kerry

Today

these are found in the remnants of old monastic settlements, often

with holy wells, with altars of loose stones called leachta,

and sometimes with rare surviving tomb-shrines (above)

and sacred (or magic) stones.

Carnacavill, county Down

These pillars can be quite small and crude - but they took considerable

effort to carve when the stone was not easily worked: flaky schists,

shales and granites are the most commonly-found in the old monastic

sites.

Saul, county Down

Lateevemore, county Kerry

But, even

in remote places, rather finely-carved pillars were put up.

Cloon West, county Kerry

There are wonderful variations on the basic designs of the Latin

and Greek (equal-armed) crosses.

Currauly, county Kerry

Gallerus, county Kerry

Non-geometric elements were introduced to the designs.

Caherlehillan, county Kerry:

a dove or peacock (symbol of immortality), and snakes or trumpets

(?)

click

for a photo taken 25 years later

Ballyvourney, county Cork:

a 'wheel' enclosing a cross-pattée surmounted by

a monk

Killaghtee, county Donegal: a 'wheel' cross

above a triple knot of Brigid

probably representing the Trinity

Cross-designs often combined

in different ways and proportions rectlinear and curvilinear elements.

Castletown, county Meath

Glencolumcille, county Donegal

Glencolumcille, county Donegal

Templastragh, county Antrim

They could illustrate ecclesiastical "tools of the trade",

such as a crozier and a Tau or T-shaped cross.

Broughanlea, county Antrim

They

could incorporate the Chi (X) Rho (P) symbol derived from the

first two letters of the Greek CRISTOS

('Christos' meaning 'anointed' - which of

course he never was: he was, famously, baptised!).

Drumaqueran, county Antrim: the Rho (P)

- a curclicue on the top arm of the cross - is the wrong way round

on one side, but the right way round on the other side of the

pillar.

photo from Trinity College, Dublin.

The Alpha (A,a) and Omega (W,w)

were also popularly incorporated, as we have already seen.

Kildreenagh, Loher, county

Kerry

Toormoor or Toormour, county

Sligo: an entirely rectilinear design which ingeniously incorporates

an Alpha (A), in the bottom half, with an Omega (w

) in the top half of the slab.

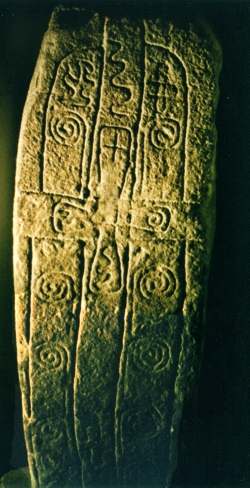

Some strikingly

incorporate Neolithic passage-tomb designs to great effect - while

also obviously influenced by the Danish-Scandinavian motifs of

Northern English 'Hogback' Stones.

Kinnitty, county Offaly

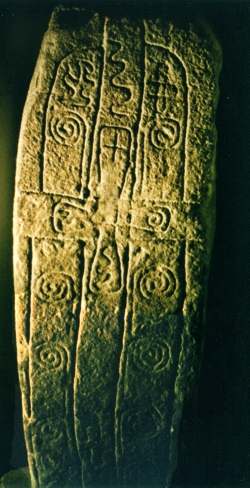

Killegar,

county Dublin

These at Killegar

are, of course, not pillars, but grave-stones in the Scandinavian

tradition.

Irish

grave-stones - or, more properly, cross-slabs - will be discussed

and illustrated on the next pages, together with the large crucifixion-slabs

which are primitive forms of the well-known sculptured or 'scripture'

crosses of the rich and richly-meadowed Midland monasteries.

![]()